Womens Work at the MoMA

May 2024 & January 2025 fieldtrips

Museum of Modern Art, NYC: Gallery 410

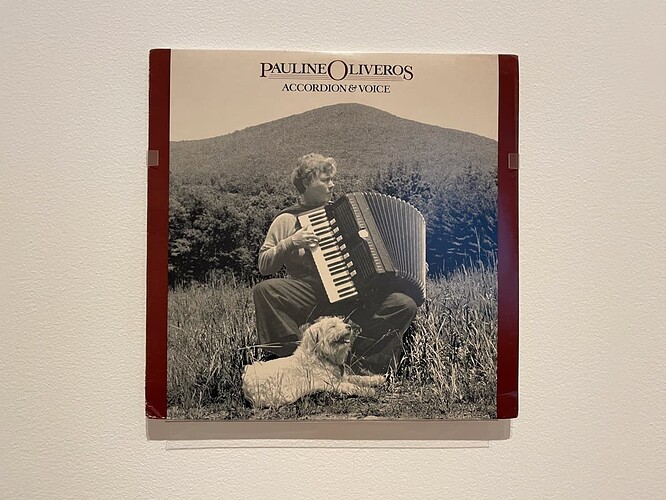

It was through Pauline Oliveros’ Accordion & Voice, 1982 that I found my way to Womens Work at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The MoMA is my neighborhood museum, and I return to experience exhibitions more than once. I’m lucky with proximity and that my aunt was in town visiting my parent on a day when I was visiting too; enjoying my art-fieldtrip storytelling led her to gift me a membership. That’s where returning to exhibitions and truly exploring art and curating (and both can lead to) becomes possible.

Pauline Oliveros: Accordion & Voice

Pauline Oliveros: Accordion & Voice, 1982, 12-inch vinyl record

Gallery label: A composer, accordionist, and educator, Oliveros has been active in the experimental and electronic music scene since the 1960s. This vinyl record is the first of her solo recordings. “Rather than initiating musical impulses of motion, melody and harmony, I wanted to hear the subtlety of a tone taking space and time to develop,” she explains. “The tones linger and resonate in the body, mind, instrument, and performance space.” Oliveros’ music encourages active, attentive, and focused listening—a central tenet of her lifelong practice and expounding of the radical potential of Deep Listening.

I think this is play, making this album was an experience of play.

Play is research with fewer guidelines.

Listening to Pauline Oliveros’ Accordion and Voice (headphones are provided), I realized that play is restorative. The presence involved in listening and responsiveness— it’s like yoga: restorative. Practicing yoga, Deep Listening, these experiences situate you in your body, in, the activity, in the world. Your mind isn’t gone. It’s just much less disembodied, less in that override mode of treating your body like a tool or machine, and the world as supplies. The more alive you are in your body—attentive, curious, experimental—the more restorative, grounding, and connecting it can be.

Animals play too.

It’s a different aspect of being.

This is not an either-or: I experience certain mental activities like planning, note-making, tracking, and reporting as emotional rest.

Neither your mind nor your body ever turn off. You can’t experience them without each other. What I’m saying is more about getting closer to presence. To what is happening here and now, to specificity, to aliveness. Of ourselves, of each other, of the world, down to the rocks.

This is not an either-or.

I love my mind, but we’ve trained for too long on distancing ourselves as if there is one final view of things that we just need to get far enough of away to see (and capture) it, and too long on isolating this from that as a way to understand what is.

So, I’m foregrounding play, embodied research. I don’t want to miss out anymore.

What does play have to do with women’s work — Womens Work?

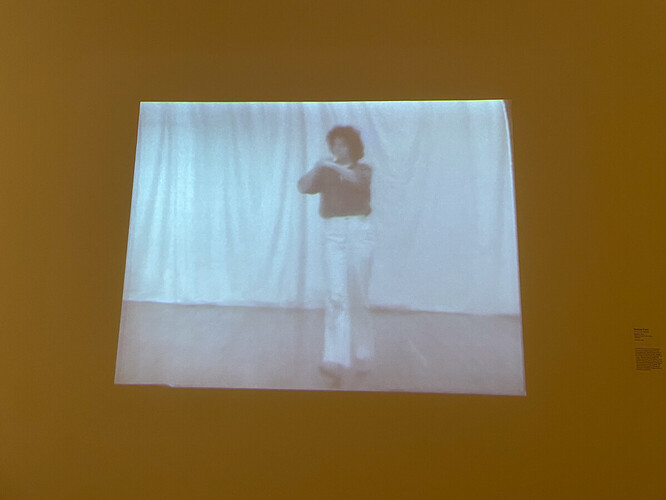

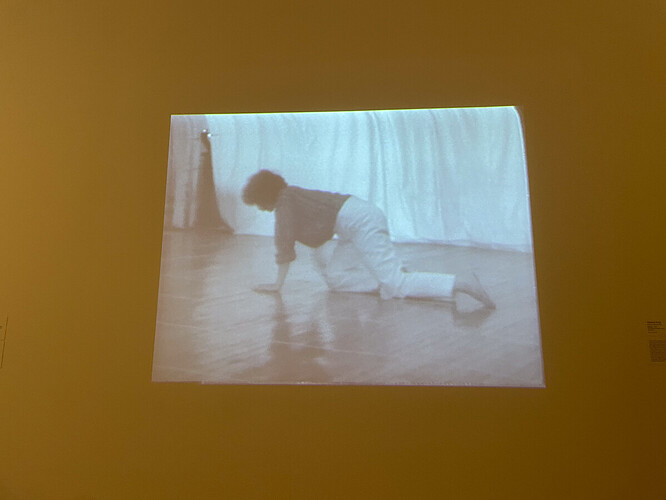

Well, play is collaborative. For Simone Forti in Solo No.1, it’s collaboration with memory and gravity. Hearing that you might ask, what isn’t a collaboration? And I would agree with you.

I wish you could see this video. There’s a couch, so you can sit. I did.

Simone Forti: Solo No.1

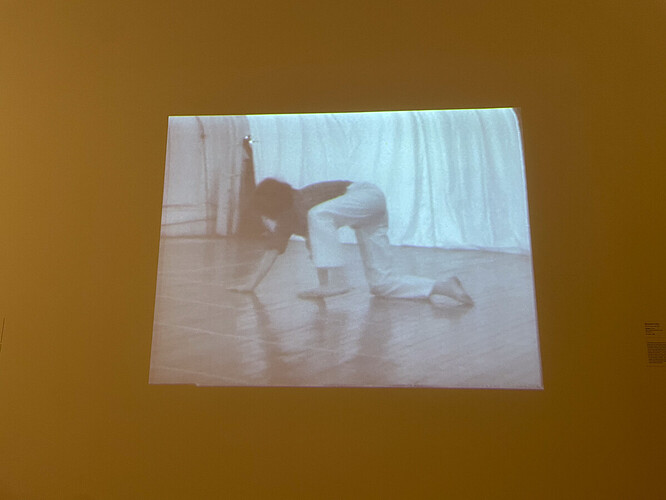

Stills from Simone Forti: Solo No.1, 1974, Video (black and white, sound) 18:40 min.

Gallery label: Forti built her practice from her interest in dance techniques. “We didn’t have to dance on a stage; we didn’t have to leap; we didn’t have to wear certain kinds of costumes,” she recalls. “We were artists working in the medium of movement.” From Solo No.1, Forti carefully observed animals, often in the zoo. She is here seen imitating the movements of various animals—walking, crawling, and rolling—to create a study in how gravity, momentum, and shifts in weight impact the body and its movements.

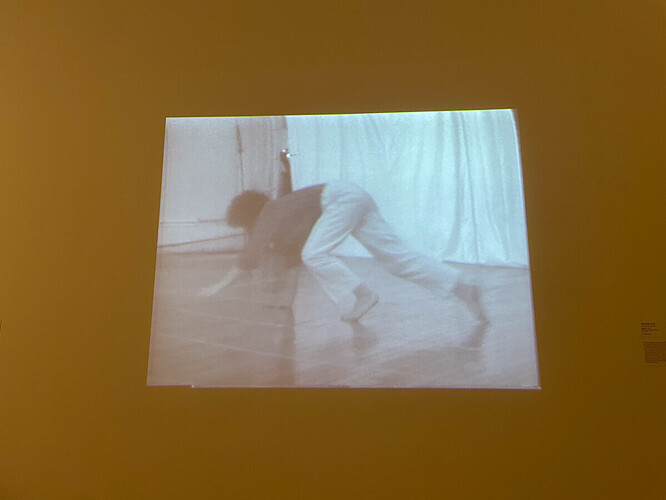

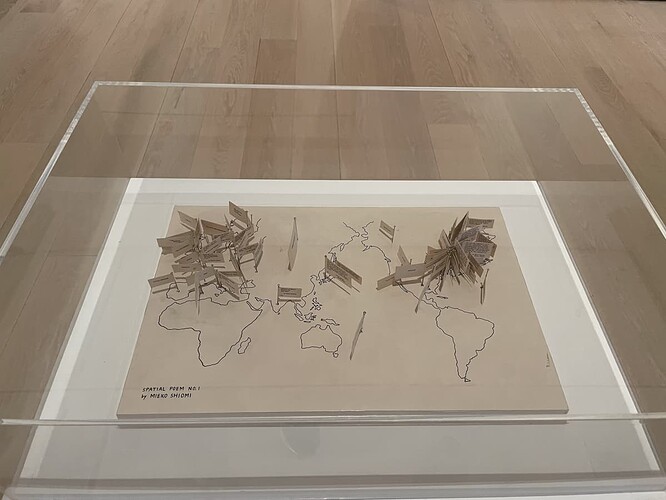

Simone Forti: Notebook - See Saw Notes

In “Notebook - See Saw Notes”, it’s easier to see the relevance of play in the familiarity of a playground toy: “Just some see sawing”

But then, the piece is instructional —

“Try sitting sideways. You’ve got the smaller weight of your arms, you can calibrate more detail.” Simone

And instructional is often associated with constriction, where constriction is categorically a bad thing (Don’t tell me what to do!). Or with work, in a work vs play binary. Or an instructor - instructed hierarchy.

Aren’t you curious though? Will this work? What will it feel like to do it! Get the board in balance!

Simone Forti: Notebook - See Saw Notes

Simone Forti: Notebook - See Saw Notes, 2011, bound notebook

I’m kind of falling in love with instructional performance art.

Its aliveness and specificity, emerging in the particular of each performance. The openness to what others will do, the collaboration and listening for others in order to do it, to bring it to life.

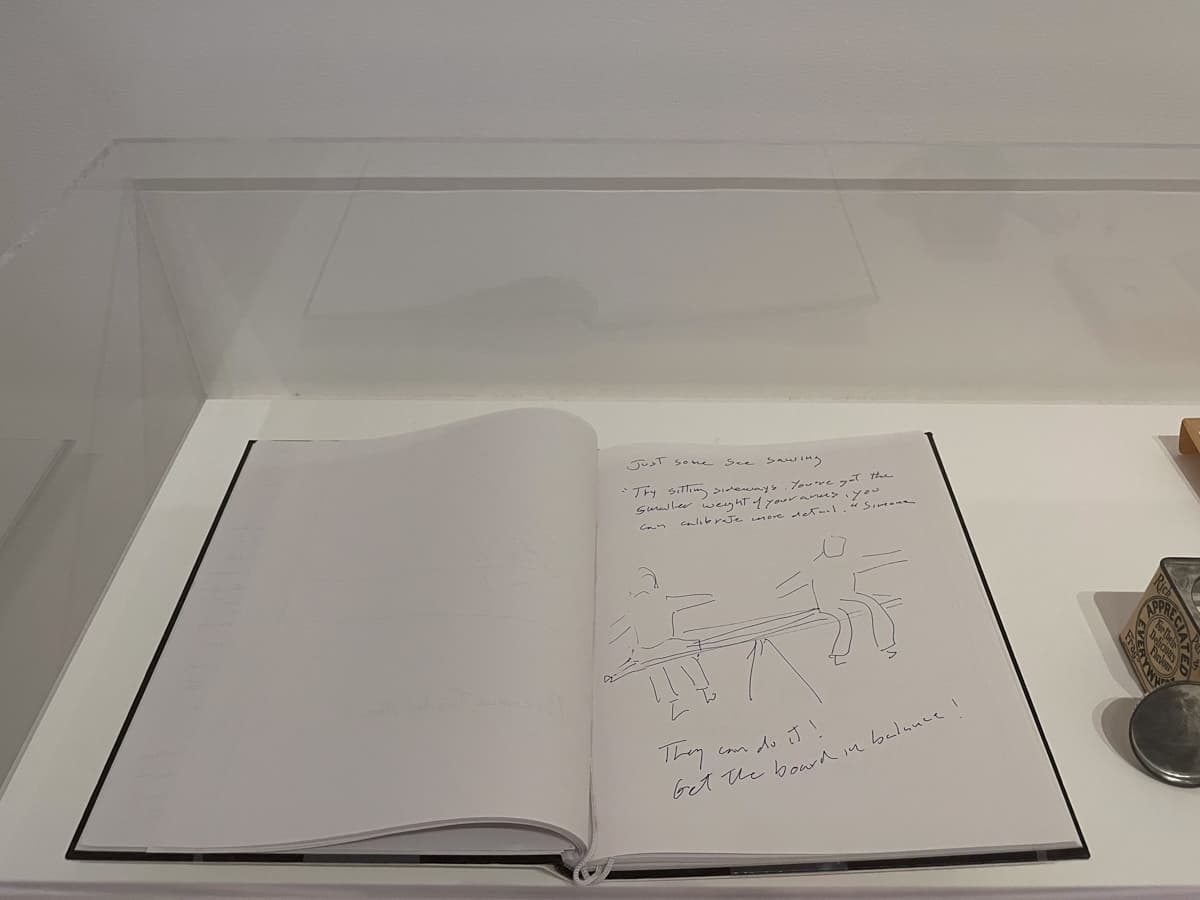

Mieko Shiomi: Spatial Poem No. 1

Mieko Shiomi: Spatial Poem No. 1, 1965, Ink and pencil on board with sixty-nine offset cards on pins, and typewriting on paper with cardboard box

Gallery label: Frustrated by the limits that geographic proximity place on the participants and audiences of art, Shiomi use the mail to connect artist and collaborators around the globe. She began this work—the first in a series of nine Spatial Poems—by formulating a prompt: “Word Event: Write a word (or words) on the enclosed card and place it somewhere. Please tell me the word and the place, which will be edited on the world map.” By soliciting outside responses, the artist relinquished authorial control and embraced chance. The resulting work is a three dimensional poem mapped across time and space.

For more on instructional performance art: Artist Instructions: These artworks aren’t finished until you participate.

It’s also the blurring of that line that typically separates art from “regular” life. That line, that makes a claim on that last step: This is creation, innovation, art, (I did it - me! I win! ) and that - all the life leading up to it, holding it, the others involved, making it possible, that is - work, maintenance, not creative less worthy.